It has to be said that Coventry isn’t one of the prettiest cities in the UK – but you can’t blame the place for that.

What was once a beautiful medieval city was bombed into near-oblivion during World War 2 – and to add insult to injury it suffered from some seriously misguided rebuilding in the 1960s, where concrete and cars were in vogue.

Here’s what I saw on a recent visit:

We were staying at the austere Ramada Hotel (left) which has a particularly grim multi-storey car park attached.

Looking over Coventry from the Ramada Hotel.

The bright red building hosts the car park for the station.

Under the flyover.

I wasn’t particularly impressed with this naff sculpture.

Street art and passers by.

There’s a LOT of car parks around Coventry.

Formerly the Tudor Rose, this faux-half timbered pub on the corner of The Burges and Corporation Street was renamed The Philip Larkin in 2017, after the poet who grew up in Coventry.

The pub has previously been known as The Tally Ho, The Wine Lodge and Eagle Vaults, and the renaming was not without controversy, given Larkin’s racist, right wing leanings.

Once owned by Coventry City fullback Big Jim Holton, The Stag on the corner of Lamb Street and Bishop Street is once again closed and boarded up after a refurb in 2018.

Mish mash of new architecture.

The Coventry Canal starts in Coventry Canal Basin and stretches for 38 miles into the Midlands’ countryside.

The first civic theatre to be built in Britain after the Second World War, The Belgrade Theatre was opened in 1958 and is now a Grade II listed building.

Wikipedia explains how it got its name:

The first steps of construction took place in 1952, when Coventry’s twin city of Belgrade, Yugoslavia (now Serbia), pledged a gift of beech timber to be used in the new theatre. It is after this city that the Belgrade is named

Some attractive elements of the past can be found amongst the grey concrete.

Coventry Basin at night.

Spon Street has some delightful medieval architecture somewhat ruined by rows of parked cars that line the street.

The interior of the Grade II listed railway station, built to the designs of W R Headley, Regional Architect of the London Midland Region of British Railways and Derrick Shorten, the project architect. It opened in 1962.

Visitor Information Borg cuboid thing.

There’s a load of new buildings going up near the station, mainly for student accommodation.

The ugly concrete heart of Coventry.

Ugly, Brutalist architecture in poor repair.

At least the colour livens up this bland covered shopping street.

Entrance to another car park.

‘The Pork Of The Town.’ Yikes.

Statue of Lady Godiva.

Managing to survive mad plans to demolish them during the post war period, these 15th-century cottages are now mainly occupied by a large branch of Wetherspoons.

Holy Trinity Church in Coventry.

The church dates from the 12th century and is the only Medieval church in Coventry that is still complete.[1][2] It is 59 metres (194 ft) long and has a spire 72 metres (236 ft) high, one of the tallest non-cathedral spires in the UK.

The church was restored in 1665–1668, and the tower was recased in 1826 by Thomas Rickman. The east end was rebuilt in 1786 and the west front by Richard Charles Hussey in 1843.

The inside of the church was restored by George Gilbert Scott in 1854. [—]

Time worn church steps.

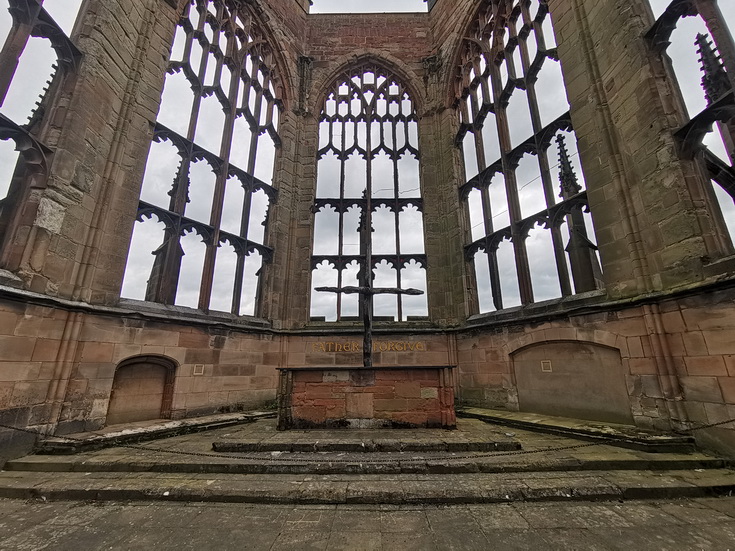

I was drawn to the famous ruins of Coventry Cathedral by the sound of bells ringing.

Known as St Michael’s, the 14th-century Gothic church was later designated as a cathedral, but was mostly destroyed after bombing during the Second World War.

With its huge open courtyard space it’s a moving place to sit and reflect on life.

The Charred Cross was created after the cathedral was bombed during the Coventry Blitz of the Second World War. The cathedral stonemason, Jock Forbes, saw two wooden beams lying in the shape of a cross and tied them together.

A replica of the Charred Cross built in 1964 has replaced the original in the ruins of the old cathedral on an altar of rubble. The original is now kept on the stairs linking the cathedral with St Michael’s Hall below. [—]

A narrow street by the cathedral provides an insight into how the area must have looked before the war.

Another car park, with this one being styled like a missile silo complete with a painting of a burning spaceship on its side,

Old and new by the railway station.